That’s equivalent to an ungodly dew point of about 95° F, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves a bit. The most humid air that occurs naturally has about 3 to 3.5% water vapor by mass. Air that has a very low content of water vapor might have only a few tenths of a percent of water vapor by mass. So water can go in and out of the vapor phase, thereby changing the properties of this stuff we call moist air. In the field of psychrometrics, however, our primary focus is on water vapor. I recently wrote about the physics of water in porous materials and there I discussed all four phases of water. (Although you dry climate folks might have difficulty believing, that photo above is dew I found on the top of my car one summer morning.) When the sun hits the grass later in the morning, the dew starts evaporating and will have all returned to the air after a while. When the temperature drops at night, we wake up in the morning to find dew on the grass and on our cars.

They don’t condense out of or evaporate into the air.īut that’s exactly what water vapor does.

The dry air components don’t change phase at the normal temperature and pressure ranges we deal with.Īs long as the temperature is above about -100° C (-148° F), all of the dry air components exist in the gas phase only. It’s also the thing that distinguishes dry air from water vapor. The table below shows the major components and a few minor ones, too.Įach of those elements and compounds has its own set of properties but there’s one important thing they have in common. Let’s take a look at the two components now. The two components, dry air and water vapor, have different properties, with one thing in particular making this mixture of supreme importance in meteorology, air conditioning, and other areas. Now, if we can just get a handle on those two things, we’ll be ready to begin.įirst, we know that moist air is a mixture. Moist air – a mixture of dry air and water vapor also known simply as “air” Again, though, we need a definition before we can advance. So, that term, “properties of moist air” is our focus, and it’s a term loaded with meaning and implications. Today I’m going to stick to covering the absolute fundamentals and save the explanations of the various psychrometric quantities and processes for a future article.

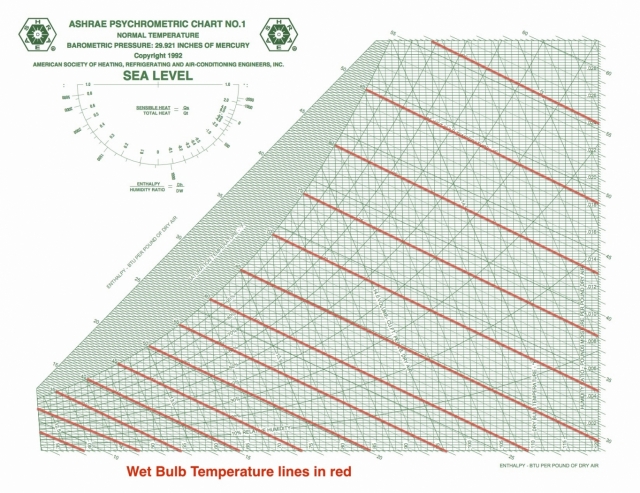

Psychrometrics – the science that involves the properties of moist air and the processes in which the temperature or the water vapor content or both are changed The bible of psychrometrics, on which I’m basing a lot of what I’m telling you here, is the book, Understanding Psychrometrics by Don Gatley. My purpose here is to define the basic terms and put the field of psychrometrics in its proper context for you. You’ll find out why in part 2 of this series.) Unless you’re an engineer, physicist, or meteorologist, your first encounter with the field of psychrometrics may have been the psych chart itself, with a little explanation of how it relates dry bulb temperature, relative humidity, dew point temperature, and “absolute humidity.” (I put that last term in quotes for a reason. One of the problems with learning this subject is that a lot of people jump straight into the chart without understanding exactly what psychrometrics is.

Well, at least it is to me, and maybe it will be to you, too, after you get to know it a bit better. And the psychrometric chart, in all its many manifestations and with its multitudinous quantities, is a thing of beauty. I have a confession to make: I’ve fallen in love with psychrometrics! After water itself, moist air has got to be the most interesting substance in building science.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)